If you send marketing messages in or to residents of Australia, you need to comply with the country's Spam Act 2003.

It has specific measures to achieve three main principles:

- Make sure you have permission before sending messages

- Identify yourself as the sender

- Make it simple to unsubscribe.

Here's what you need to know about the Spam Act 2003 and how to compy with it.

- 1. Background to the Spam Act 2003

- 2. Scope of the Spam Act 2003

- 3. Getting Permission to Send Messages

- 3.1. Express Permission

- 3.2. Inferred Permission

- 4. Identifying Yourself in Messages

- 5. Making it Easy to Unsubscribe from Messages

- 6. Penalties for Breaching the Spam Act 2003

- 7. Other Considerations for the Spam Act 2003

- 7.1. Address Harvesting

- 7.2. General Behavior

- 7.3. Privacy Act

- 8. Summary

Background to the Spam Act 2003

The Spam Act 2003 is a federal law that took effect partially in 2003 and in full from 10 April 2004. It's enforced by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA).

The original Act has not been amended since its introduction. However, under Australia's legislative system, the Act's measures and how they work in practice were clarified by the Spam Regulations of 2004. These were repealed and replaced by the Spam Regulations of 2021. The new regulations strengthen the way the original measures are implemented in practice.

Scope of the Spam Act 2003

The Spam Act 2003 covers unsolicited commercial electronic messages with "an Australian link."

Electronic messages include (but are not limited to) emails, SMS text messages, multimedia text messages and instant messages.

The key principle of the "commercial" definition is to cover marketing and promotional messages.

The Act specifically exempts several types of message from the definition:

- Messages that are purely factual information (with no promotional element)

- Messages sent or authorized by a government body, political party or charity about goods or services which it is (or may be) supplying

- Messages sent or authorized by an educational institution to a current or former student, about goods or services which it is (or may be) supplying

The safest approach is to assume that any message that promotes a product or service comes under the Act.

"Australian link" is broadly defined and covers any of the following situations:

- You send the message from Australia

- The individual who sent or authorized the message is in Australia when it is sent

- The organization who sent or authorized the message has its "central management and control" in Australia

- The message is accessed on a device or server in Australia

- The recipient is a person in Australia when they access the message

- The recipient is an organization that does business in Australia

Getting Permission to Send Messages

The Spam Act 2003 says you must have permission before sending a message. This permission can be express or inferred. In both cases, it's up to you to prove the consent.

This means it's sensible to keep a record of either when and how somebody gave permission, or how you determined that inferred permission was appropriate.

Express Permission

Express permission applies where the person has expressly consented to receive marketing messages. The Act doesn't specify how this consent can be given, so possible ways include:

- Ticking a checkbox on a form

- Giving verbal consent

- Giving written consent

Whichever method you use, you cannot send an electronic message such as an email asking somebody to consent. That's because this message itself counts as a commercial electronic message under the Act and regulations. By definition, you don't have the necessary consent to send this message.

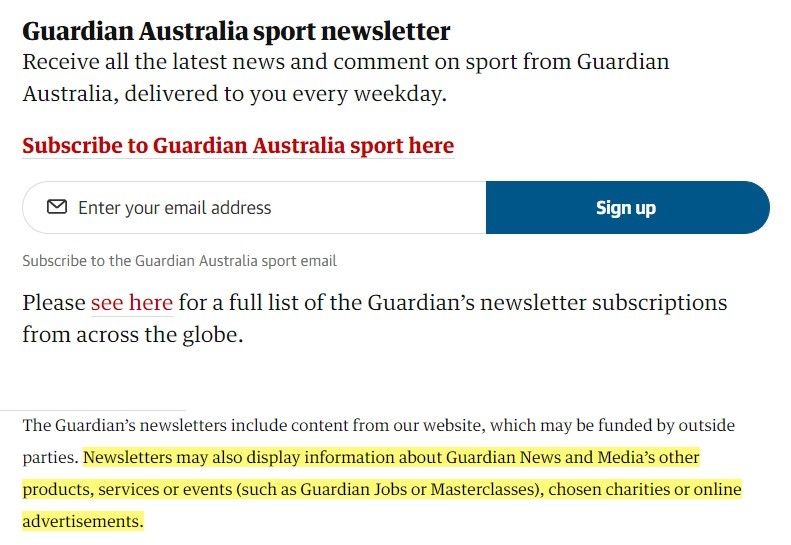

Guardian Australia tells people signing up to an email newsletter that it may include commercial content. It will then treat anyone who chooses to sign up after seeing this notice as having given express permission:

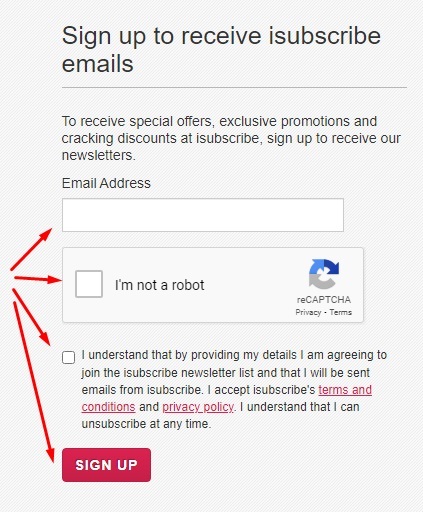

The sign-up form for isubscribe not only notes that it involves commercial messages, but requires the user to take four actions (type e-mail, complete CAPTCHA check, tick box, click sign up button), removing any risk of an accidental signup or confusion:

Inferred Permission

You can infer permission to send emails. When this appropriate and valid is less clear-cut than using express consent, but as general principle inferred permission is acceptable only if:

- You have an ongoing relationship with the recipient (and can prove this is the case), and

- The messages you send are directly related to this relationship

In most cases the person will have taken a step to establish this ongoing relationship such as starting a subscription, becoming a member or opening an account.

Inferred permission isn't appropriate where somebody has simply made a purchase and you want to send them promotional messages to encourage further purchases.

A 2006 court case ruled that you cannot simply send messages and then treat the recipient's failure to exercise an opt-out method as inferred permission. That's because you must have a clear basis of permission (either express or inferred) before sending any message.

Identifying Yourself in Messages

The Spam Act 2003 says commercial electronic messages must clearly identify who sent the message (or who authorized its sending if that's different).

The message must also include contact details for the sender (or the person or organization that authorized the message).

The Act says the identity and contact details you provide must be "reasonably likely to be valid for at least 30 days" after you send the messages. For example, you can't give a phone number and then stop using it right after sending out a batch of messages.

The ACMA recommends that you either give the legal name of the business, or that you give your own name and your Australian Business Number.

The Conversation identifies itself as sender and includes its contact details:

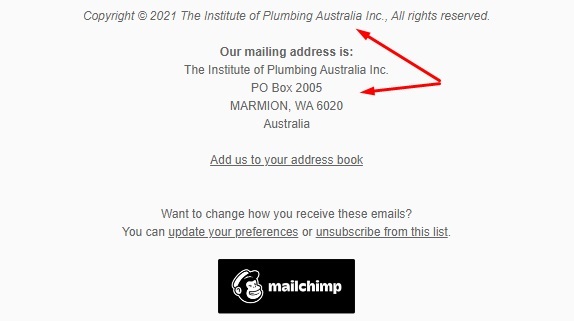

The Institute of Plumbing Australia includes the details alongside its copyright and unsubscription notices in its email newsletter:

Include as many contact methods as you have available, from an email address and mailing address, to a phone number and online contact form.

Making it Easy to Unsubscribe from Messages

The Spam Act 2003 says commercial electronic messages must include an unsubscribe option. Specifically, the message must include a "clear and conspicuous" statement that:

- Tells the recipient they can unsubscribe by sending a message, and

- Gives an electronic address (such as an email or text message number) to send the unsubscribe message

You must be the person or organization that operates this address and it must be "reasonably likely" that you will receive messages at this address for at least the next 30 days.

Although the original wording of the law refers to sending a message, a one-click unsubscribe button in an email appears to meet the spirit and broad principle of the law, if not its precise wording.

The "simplified outline" included in the text of the law says "Commercial electronic messages must contain a functional unsubscribe facility."

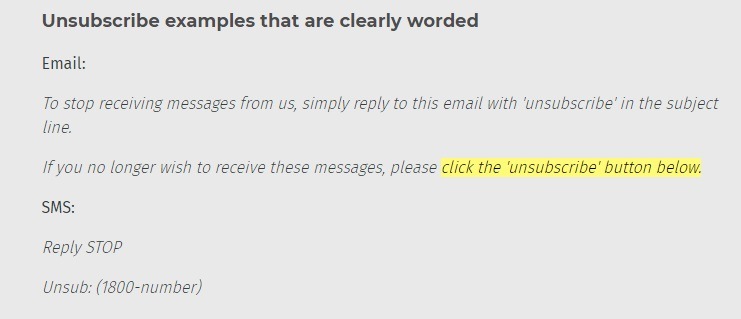

ACMA's examples of clear wording suggest an unsubscribe button is adequate:

Down Syndrome Australia's email newsletter offers a button and an email address to unsubscribe:

The Spam Regulations 2021 set out more specific requirements for the unsubscribe process, including:

- You must honor unsubscription requests within five working days and stop sending commercial electronic messages

- You cannot charge people a fee to unsubscribe

- You cannot use an electronic address with a premium cost, for example a phone number for text messages. The cost of sending the message cannot be more than usual for that means of communication.

- You cannot require people to create an account, log in to an account, or provide further personal information in order to unsubscribe

Penalties for Breaching the Spam Act 2003

The ACMA has the power to take several actions against those who violate the Spam Act 2003. The most serious is to pursue financial penalties in federal court.

As with many laws in Australia, the maximum penalty is laid down as a number of "penalty units." The dollar value of each penalty unit changes over time, for example to reflect inflation.

The maximum penalty depends on whether you are an individual or a business (a "body corporate"), which rule you break, and whether or not this is the first penalty you have received under the Act.

There's also a cap on the total fines imposed for breaches that happened on the same day. This means the biggest possible fine would be for a business that carried out multiple breaches on the same day and was a repeat offender. In this case, the maximum penalty would be 10,000 penalty units which, at the time of writing, equals AU$2.2 million.

The highest fine actually imposed to date was a little over AU$1 million to Woolworths for sending messages to customers who had already unsubscribed. Meanwhile, Optus was fined AU$504,000 for sending messages to customers who had unsubscribed and sending messages without an unsubscribe option.

The federal court also has the ability to make offenders pay compensation, or pay a fine equal to the profits they made as a direct result of breaching the Act.

The ACMA can ask the federal court to impose an injunction stopping a business from taking actions that breach the Spam Act 2003.

Businesses may make formal undertakings with the ACMA to stop particular behavior. This could result in a reduced financial penalty for the original offense. These undertakings are then legally enforceable.

Other Considerations for the Spam Act 2003

Address Harvesting

The Spam Act 2003 completely bans address harvesting software. This is software that automatically "crawls" web pages looking for email addresses and then collects them to produce a mailing list.

The Act not only says you must not acquire, supply or use such software, but also that you must not acquire, supply or use mailing lists produced by such software.

This ban applies regardless of whether you have express or inferred consent from anyone whose address is on the list.

Note that the Act doesn't ban buying address lists gathered through means other than address harvesting software. However, you remain responsible for ensuring you have express or inferred permission to email people, so bought lists may be impractical to use.

General Behavior

The rules under the Spam Act 2003 are broadly applied. This means you can't take actions such as helping or encouraging somebody to break the rules and then argue you didn't technically break the rules yourself.

Privacy Act

Most commercial electronic messages also come under Australia's Privacy Act because they inherently involve processing personal data (including the recipient's email address). This can cause confusion as the Privacy Act allows direct marketing on an opt-out rather than opt-in basis.

However, there is no conflict between the two laws in practice. Even if you have legally gathered personal information and have the right to use it for direct marketing (because the person has not actively opted out), you cannot send a commercial electronic message to the person without either express or inferred permission.

Although some consultation participants have suggested a "bundled consent mechanism," at the moment you must get separate, specific consent under the two laws: to collect and use data (in some circumstances) under the Privacy Act, and to send messages under the Spam Act 2003.

Summary

Let's recap what you need to know about the Spam Act 2003:

-

The Act applies when you send commercial electronic messages with an "Australian link."

- This includes emails, SMS and multimedia messages, and instant messages.

- It covers most messages that promote a product, service or business.

- "Australian link" covers messages sent to or from Australia, accessed in Australia, or sent by an Australian business

- You must get express or inferred permission before sending commercial electronic messages.

-

Express permission means the person has demonstratively given explicit consent to receive the messages.

- Inferred means you have an ongoing relationship with the recipient and the messages relate to that relationship. Somebody simply buying something from you does not qualify as an ongoing relationship.

- The message must include your identity and contact details, which should be valid for at least the next 30 days.

-

The message must include an unsubscribe option. You must give an address (such as email or phone number) and tell people they can send a message to this address to unsubscribe.

- The address must be valid for at least the next 30 days.

- You can't charge an unsubscription fee, use a premium rate number, or require somebody to create an account to unsubscribe.

-

The maximum penalty for breaches depends on whether you are a business or individual, which rules you break, and whether you have broken the rules before.

- In theory a business could face a maximum fine of AU$2.2 million for each day on which they broke the rules. The record fine so far is $1 million.

- The Spam Act includes an outright ban on buying, selling or using address harvesting software.

- The Privacy Act applies to most electronic messages. However, the fact it uses an opt-out system for processing personal data does not override the Spam Act's opt-in system for permission to send messages.