While the GDPR has made the headlines, another major European Union law affecting electronic communications is in the works.

The ePrivacy Regulation would expand the scope of privacy rules, react to technological changes, and alter the rules for cookies and spam.

Here's what you need to know about how the rules may change, and what it means for your business practices.

- 1. Background to the ePrivacy Regulation

- 2. How the ePrivacy Directive Works With Other Laws

- 2.1. Regulations & Directives

- 2.2. The GDPR

- 2.3. United Kingdom

- 2.4. The Existing Rules

- 3. The Content of the ePrivacy Regulation

- 3.1. Scope of the ePrivacy Regulation

- 3.2. Key Principles of the ePrivacy Regulation

- 3.2.1. Exemptions

- 3.3. Terminal Equipment

- 3.4. Cookies

- 3.5. Direct Marketing

- 4. Enforcement of the ePrivacy Regulation

- 5. Summary

Background to the ePrivacy Regulation

Until 2018, European privacy rules came from two main sources:

- The 1995 Data Protection Directive, which covered data protection as a whole

- The 2002 Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive, which added specific rules for online communications

European politicians then decided both sets of rules needed updating and toughening up. From 2018, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) replaced the Data Protection Directive.

European politicians had originally planned to replace the Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive with the ePrivacy Regulation at the same time as the GDPR changes. However, the content of the Regulation has to be negotiated between the European Parliament and the national governments of the relevant countries.

This was severely delayed as different national governments had different ideas about what should be in the Regulation.

In February 2021 the governments announced they had reached a broad compromise on what they wanted and what they would accept.

Although the final Regulation must still be negotiated, it's now considerably more likely that it will take effect in the coming years.

We also have a much better idea of the key points it will likely contain.

How the ePrivacy Directive Works With Other Laws

Regulations & Directives

The system of European Union rules and laws can be confusing but it's simpler when you understand a key distinction:

A directive is an agreed set of legal principles and measures. It doesn't have direct force itself, but every European Union country must pass its own national law that covers the directive's principles and measures.

A regulation has direct legal force in all European Union countries without the need for passing a national law.

The main practical differences for business are that a regulation gives more certainty about the rules as they are the same in every country. The rules will also take effect at the same time in every country rather than depending on the legislative process in each country.

As things stand, the ePrivacy Directive would have legal force two years after it gets final approval.

The GDPR

Because they cover some of the same areas, it's possible the same case could be covered by both the existing GDPR and the new ePrivacy Regulation. This would be resolved by a legal principle called lex specialis.

This would mean the ePrivacy Regulation would normally take priority over the GDPR because it is designed to cover a narrower, more specific area of law.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom left the European Union in January 2020. To simplify the process, it decided that all European Union regulations in force at this time would automatically become part of its national laws.

This means that unless and until the UK changes its laws, the measures of the GDPR still apply if you, the data subject (the person the data is about) or the data processing is in the UK.

Contrastingly, the ePrivacy Regulation would not have legal force in the UK. It is possible the UK government could decide to create a national law mirroring the ePrivacy Regulation but it is under no obligation to do so.

The Existing Rules

Before breaking down the ePrivacy Regulation changes, let's run through the key points of the existing 2002 Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive.

Remember that these points are actually enforced through a different national law in each country, so the specific details may vary from case to case:

- You must delete or anonymize most data when you no longer need it. You can only keep data for future marketing if you have consent.

- You can normally only send unsolicited marketing emails (spam) where the user has opted in to the possibility of receiving such messages.

- You can use strictly necessary cookies such as those in a virtual shopping cart. Other cookies require consent based on "clear and comprehensive information." This has to be opt-in, meaning active consent. The directive doesn't set out specific technologies for complying with these rules.

The GDPR reinforces and builds on some of these principles:

- Email addresses are personal data under the GDPR. Cookies can be personal data if they can be linked to an individual.

- The main lawful reasons to use personal data are that you have consent or that you do so to serve your legitimate interests (and doing so doesn't outweigh the person's data rights).

- You can only use data for the purpose you stated, either when gathering consent or when concluding that your legitimate interests were valid.

- Consent must be active and meaningful. Regulator and court decisions have clarified that this means you can't use opt-out/implied consent, pre-ticked consent boxes, or cookie walls (where users can't access a site unless they agree to cookies).

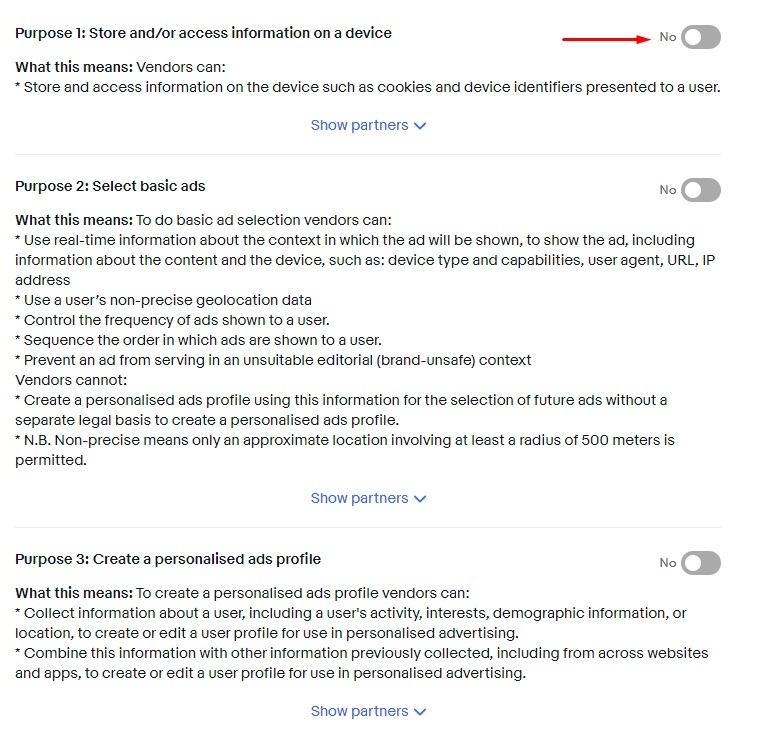

CNN uses a pop-up message to run through the key data it collects through cookies and how it uses it. It gives a choice between accepting all cookies or deciding which to reject, though the latter option could be made more prominent:

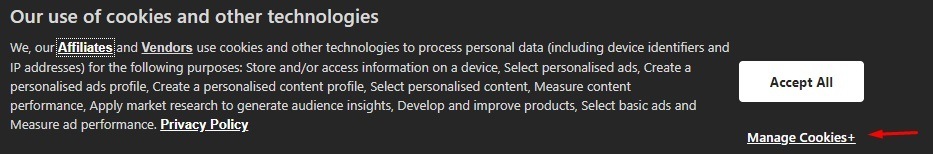

eBay complies with the GDPR by having its slider options set to No (refusing consent) by default:

Let's see what new requirements the ePrivacy Regulation proposes.

The Content of the ePrivacy Regulation

The ePrivacy Regulation has two main aims:

- To update the 2002 Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive to reflect changes in technology

- To build upon the GDPR with specific rules and clarifications to cover data in the context of electronic communications

In some cases, the proposed changes reduce the burden on website operators or give them more leeway.

We've detailed below the key points in the latest draft of the Regulation. It's possible some of the specific details may change, but the broad principles are likely to be in the final version if and when it takes force.

Scope of the ePrivacy Regulation

The geographic scope of the ePrivacy regulation is narrower than that of the GDPR. It applies when the end user (that is, the data subject) is in a European Union country. It doesn't matter where the data controller is located or based, or where the processing takes place.

The Regulation covers any electronic communications data sent over a publicly available network or service. This includes data sent between machines (for example through devices using the "Internet of Things"), not just data sent between users.

It doesn't cover communications over networks or services that aren't publicly available, for example between devices on a local Wi-FI network or intranet.

The rules won't apply only to the content of electronic communications, but also to the associated metadata. This includes information about the sender and the recipient, the time the data was sent, the devices used, and the size of any files.

Unlike the GDPR, which only applies to natural persons (humans), the ePrivacy Regulation covers the privacy of legal persons (such as corporations) as well. It does not cover deceased persons.

Key Principles of the ePrivacy Regulation

The key principle of the ePrivacy Regulation is the presumption of confidentiality. This means all electronic communications data must be treated as confidential unless the directive says otherwise. This means no processing, accessing or intercepting the data.

Exemptions

Some of the key exemptions to the confidentiality principle are as follows.

- Processing of any data with the user's consent for a specified purpose

- Processing of any data to protect the "integrity" of communications services, for example checking for malware

- Processing of any data to comply with a law

- Processing of metadata for operating purposes such as calculating bills or detecting fraud

- Processing of metadata for infrastructure and planning, for example in deciding where to build or upgrade broadband networks. (This processing would require consent.)

- Processing of metadata to protect peoples' vital interests, for example dealing with a disaster or epidemic.

Terminal Equipment

The ePrivacy Regulation has special rules for data stored on the user's "terminal equipment." This means any device connected to the Internet, including computers, tablets, phones and routers.

The rules say that you cannot do any of the following without consent or for other limited reasons.

- Process data on the device

- Store data on the device

- Collect data from the device

In simple terms, the limited reasons to do this without consent are that it is necessary to provide a service requested by the user either on a site (such as a virtual shopping cart) or on physical devices (such as a smart meter for utility supply). This activity must have at most a "very limited" intrusion on privacy.

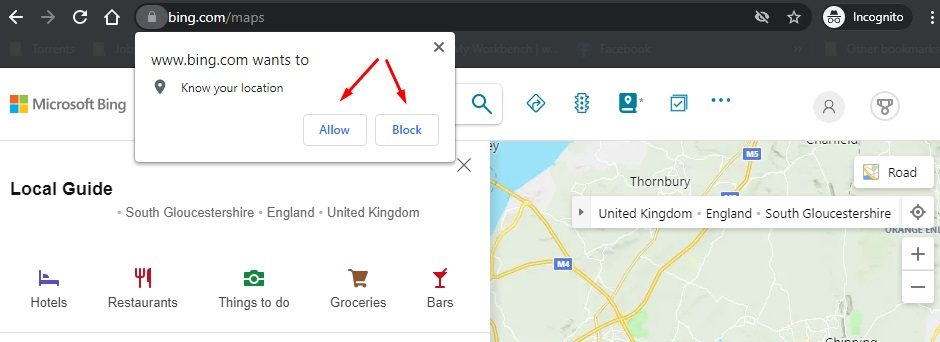

Getting consent can sometimes be simple. This is how Bing (using Chrome's settings) asks for consent to collect data from a device to determine the user's precise location:

Cookies

Previous GDPR regulator and court rulings have confirmed that consent is only meaningful when user's have a genuine choice whether to give it. The ePrivacy Regulation will set out in law that this applies to cookies.

The previous rulings established that sites don't comply with the GDPR if they use a cookie wall. This is where users must consent to non-essential cookies to be allowed to access the sites.

The ePrivacy Regulation will clarify that sites can combine a paywall and a cookie wall. In other words, they can give users a choice between paying to access a site (or a section of a site), or getting the access in return for accepting non-essential cookies or similar data use.

However, this isn't allowed where there's a "clear imbalance" between the service provider and user. For example, it wouldn't be allowed where the site is operated by a public authority and is the only way to access a public service.

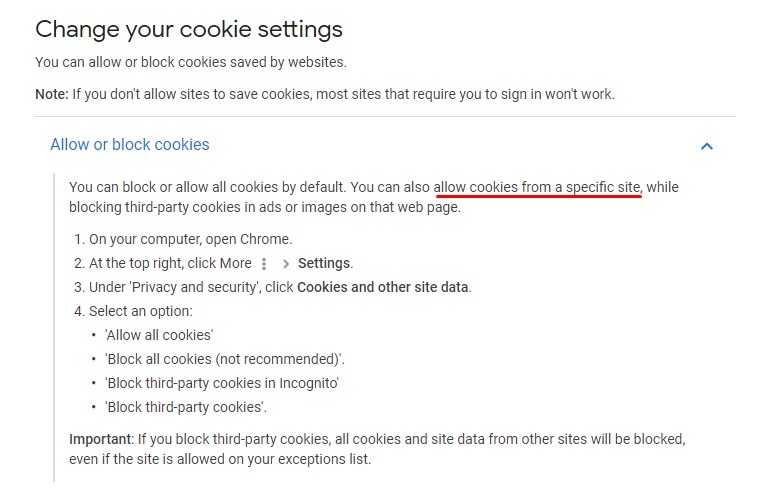

The regulation clarifies it is lawful for sites to refer to cookie choices that users have made in their browser settings. For example, this could include "whitelisting" to automatically consent to all cookies from a particular provider (such as a third-party advertising network).

The regulation encourages this practice as a way to reduce the number of occasions users are asked to make cookie choices, which can undermine the consent process by making them more likely to simply click through without reading.

Google explains how to whitelist sites in the Chrome browser. Under the ePrivacy Directive, whitelisted sites can treat this setting as consent:

Direct Marketing

Under the ePrivacy regulation, it's normally only legal to send direct marketing (including emails) to somebody with their prior consent.

The Regulation does say that if a customer makes a purchase, you can use their contact details to market similar goods and services to them later on.

However, you must give the user a clear and easy way to object to this marketing, not only when you first collect their contact details, but every time you send them marketing messages.

Individual EU countries will be able to make laws that put a time limit on sending marketing messages after a purchase.

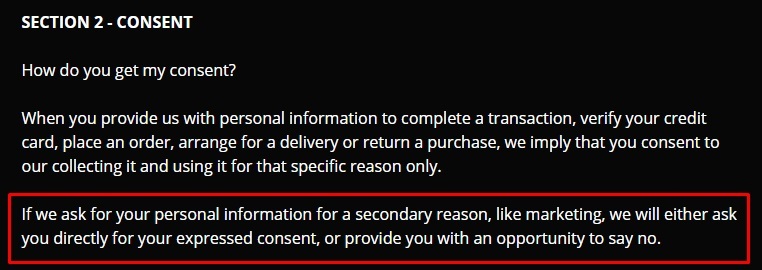

This change would affect the Privacy Policy of Paradise Cycles, which lists two ways it may determine consent for marketing. Under the GDPR, it must rely on the first way (expressed consent.) Under the ePrivacy Directive it could rely on the second way (giving an opportunity to say no):

This exemption only covers using the contact details for your own marketing. You can't share the details with a third party or use them to send marketing messages on behalf of a third party.

Enforcement of the ePrivacy Regulation

The ePrivacy regulation would be enforced in a similar way to the GDPR with each country having one or more supervisory authorities, cooperating through the European Data Protection Board.

The maximum fine for breaching the ePrivacy Regulation is €10 million or two percent of a business's annual turnover, whichever is bigger.

A supervisory authority can order a business to take an action or change its behavior following a breach. Refusing to follow this order can mean a maximum fine of €20 million or four percent of a business's annual turnover, whichever is bigger.

Individual countries can set out their own rules for penalties other than fines. This could include a temporary or permanent restriction on data processing.

Summary

Let's recap what you need to know about the ePrivacy Regulation.

- The ePrivacy Regulation is a proposed European Union law. It would have legal effect in all European Union countries two years after it passes. It would not apply to the United Kingdom.

- The Regulation would replace the 2002 Privacy and Electronic Communications Directive. It would work alongside the GDPR and would take priority if the two regulations conflicted.

- Unlike the GDPR, the ePrivacy Regulation would only cover cases where the end user (the data subject) is in a European Union country.

- The Regulation covers both data and metadata sent over a publicly available network. It covers data about living people and "legal persons" such as a corporation.

-

The main point of the Regulation is that you cannot process, access or data without consent. Key exemptions include:

- Processing data to check for malware or comply with the law

- Processing metadata to calculate bills, detect fraud, or protect people's vital interests

- The Regulation also says you cannot process or store data on a user's device or collect data from a user's device without consent unless you need to do so to provide a requested service.

- The Regulation confirms user consent for cookies must be based on a meaningful choice.

- You can't make consent to non-essential cookies the sole condition for accessing a site (a cookie wall). You can make it an alternative to paying for access (a paywall), though this isn't allowed for some sites such as a public authority offering a service to citizens.

- If you collect customer contact details for a purchase, you can use them to send messages marketing your own products and services. You don't have to get specific consent but you must offer customers a chance to opt-out, both when you collect the contact details and every time you send a marketing message.

- The maximum penalty for breaching the ePrivacy Regulation is €10 million or two percent of a business's annual turnover, whichever is bigger.

- Supervisory authorities can order you to take or cease actions after a breach. Defying this order can lead to a penalty of €20 million or four percent of a business's annual turnover, whichever is bigger.